Federico Barocci

Federico Barocci

Urbino 1535 - 1612

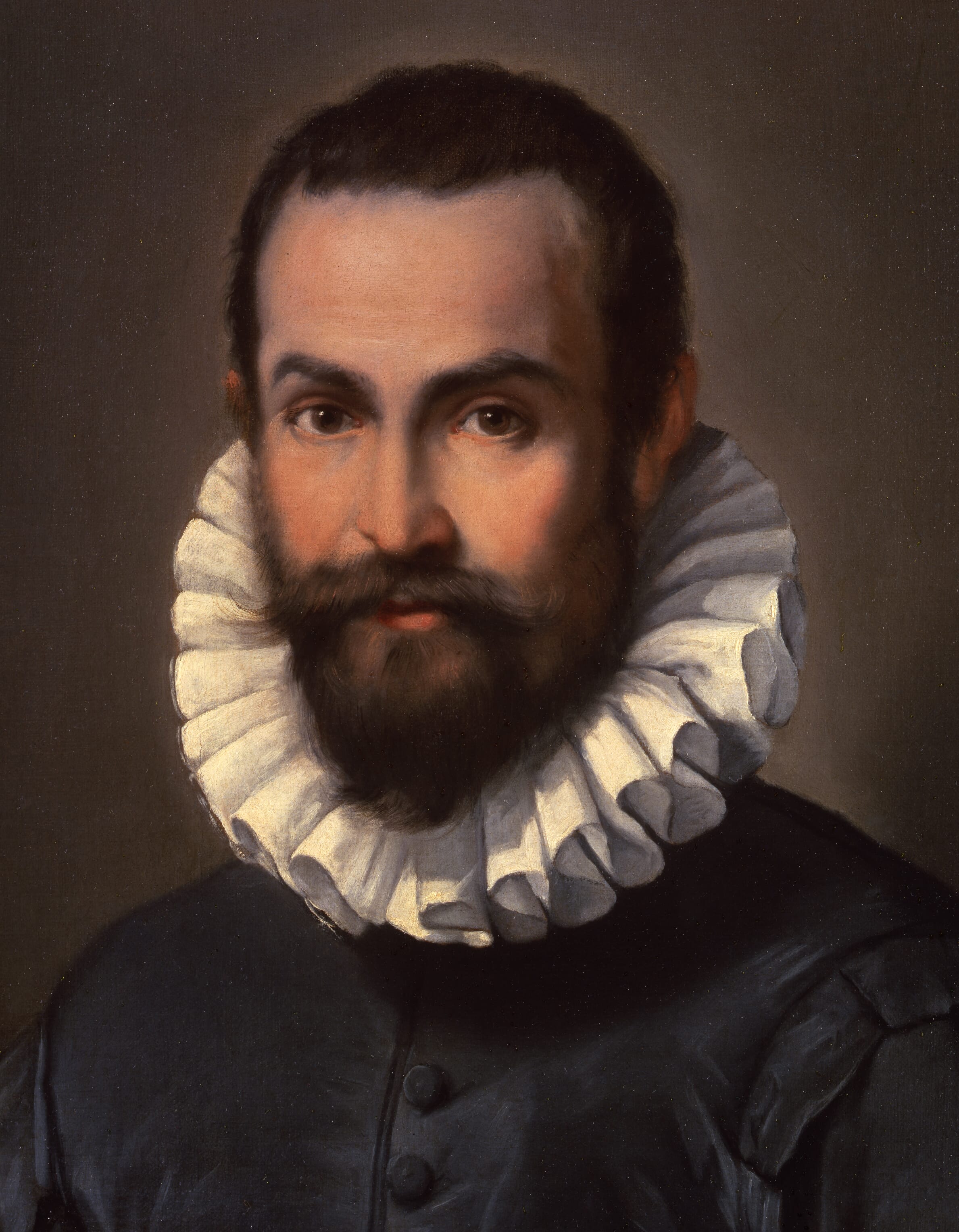

Portrait of a Gentleman | Portrait d'un gentilhomme

Oil on canvas

54,3 x 42,5 cm (21 3/8 x 16 ¾ in.)

Provenance:

Christie's London, 3 December 1997, lot 35; Jean-Luc Baroni, London; private collection, France.

Literature:

Jean-Luc Baroni, Master Paintings, 1998, no. 6; Nicholas Turner, Federico Barocci, Adam Biro, 2000, p.126, illustrated p.125, fig. 113.

Exhibition:

From January 2006 to March 2019, on loan from the owner to the Musée de Beaux-Arts in Lyon for public exhibition.

The Barocci family had settled in Urbino in the second half of the fifteenth century, when its founder Ambrogio Barocci was summoned to participate in the decoration of the Palazzo Ducale. Many generations of the family had been craftsmen and astronomers. Ambrogio Barocci the Younger, the grandson of the founder, made a successful career in Urbino as 'a maker of molds, relief models, seals and astrolabes', but his son Federico, although initiated to his father's trade, vowed to dedicate himself to painting. He entered the studio of the Venetian Battista Franco, who came to Urbino around 1545 after having worked in Rome. After his departure, Barocci continued his training in Pesaro with his uncle, the architect Bartolomeo Genga, who helped him perfect his knowledge of 'geometry, architecture, and perspective, in which disciplines he became erudite.' [1]

Two journeys to Rome, one around 1550-1555 and the other in 1560-63, completed his training. In the Eternal City, Barocci quickly gained respect and admiration. His acquaintance with Taddeo Zuccaro and the support of the cardinal Giulio della Rovere helped him obtain important commissions, the most remarkable of which was certainly his decorations on the theme of the life of Christ in the so-called Casino of Pius IV, which was built in the Vatican gardens by the architect Pirro Ligorio. The success of these decorations, even before they were finished, attracted the envy of rival painters who poisoned him. Barocci never fully recovered after this incident and his health remained frail thereafter. The artist returned to Urbino and although he rarely left his native town again, with the support of the duke Francesco Maria della Rovere he received numerous commissions for churches in the Marches.

Barocci's fame, aided by the diffusion of prints, spread beyond the confines of Urbino and made him a sought-after artist. Thus, without the need to travel, he painted the altarpieces The Visitation and The Presentation of the Virgin for the Oratorians of the Chiesa Nuova in Rome, The Communion of the Apostles for Clement VIII, destined for the Aldobrandini chapel in Santa Maria sopra Minerva, and the superb Crucifixion for the Genoese senator Matteo Senarega which can be found in the Genoa Cathedral. Finally, he received a request of the Holy Roman emperor Rudolf II who wished to have a work by his hand which Francesco Maria Della Rovere financed: The Flight of Aeneas from Troy (today lost, known through an autograph replica at the Galleria Borghese in Rome).

In spite of his relative isolation and poor health, Barocci was one of the greatest artists of his time. During his lifetime, his new mannerist style, the precursor of Baroque, exercised considerable influence upon all artists in the late sixteenth and seventeenth century and beyond. A prolific and exquisite draughtsman, he was able to infuse in his large-scale altarpieces a new, authentic spirituality while maintaining a remarkable finesse of conception and execution. He played an undeniable role in the development of such different artists as the Carracci, Francesco Vanni, Ventura Salimbeni, Guido Reni, Rubens, and even Bernini.

Although Barocci was mainly a religious artist, he was also a successful portraitist, which genre he practiced throughout his career. He made portraits 'in both paint and pastels which are perfect likeness of life', as Belloriwrote. [2] He executed several portraits of his patrons, including the members of della Rovere family: Giulio (today lost), Francesco Maria II (Florence, the Uffizi), Giuliano (1595, Vienna, Kunsthistorische Museum), and probably Ippolito (1602, Italian Embassy in London). Most of these portraits are grand images of rank and power where Barocci however offered deep insight into the character of the sitter, following the example of Titian, in whose work he particularly drew inspiration for the portrait of Francesco Maria II. He also painted portraits of many of his friends, whom Bellori enlisted in his book. The present fine portrait of a gentleman, whose identity remains unknown, is undoubtedly an example of this second category, given the sitter's frank gaze and his unconstrained expression. Elements of style and palette indicate that it may have been painted at about the same time as the presumed portrait of Ippolito della Rovere, that is, in the early seventeenth century. In a letter of 4 March 1998, Dr. Edmund Pillsbury, according to whom this Portrait of a Gentleman 'constitutes a major addition to the artist's small oeuvre' stated that the '...suggestion of the relationship (...) with the 1602 London portrait is intriguing and quite plausible. The opaque treatment of the white paint in the collar would seem to preclude a dating in the seventies or eighties, in any event." Nicholas Turner made the same connection and came to the same conclusion in his book dedicated to the painter.

Barocci is a rare artist and few of his paintings ever left Italy. His fame was such, however, that eight years after his death Cavalier Marino – the leading Italian poet of the 17th century – dedicated the following verses to the artist in which he placed him right after Michelangelo, Raphael and Titian and praised his ability to paint the human figure:

Il gran Barozzi è questi.

L'uccidesti Natura invida, e rea,

Perchè tolti i pennelli egli t'havea.

Invida l'uccidesti,

Chè se crear nan seppe huomini vivi,

Benchè d'anima privi,

Fece a credere altrui con color finti,

Ch'eran vivi i dipinti [3].

[1] Giovanni Pietro Bellori, The Lives of the Modern Painters, Sculptors and Architects, Cambridge University Press, New York, 2005, p. 160.

[2] Ibid, 1672, p. 192.

[3] La Galeria del Cavaliere Marino. Distinta in Pitture, e Sculture, Milan, Giovanni Battista Bidelli, 1620, p. 233: 'This is the Great Barocci./ O jealous and guilty, Nature! You killed him,/ Because he had taken your brushes from you./Jealous, you killed him,/ Because although he could never create living men,/ Even though without a soul,/ He made others believe with counterfeit colours,/ That his paintings were alive.'